How should Biden's first 100 days as US president be judged?

"Biden is very much in that tradition, and he is exposing himself to that comparison," Michael Rockland, a professor of American studies at Rutgers University, told The New Arab. "Whether or not you agree with Biden, he's certainly taking a stand."

Laying a foundation

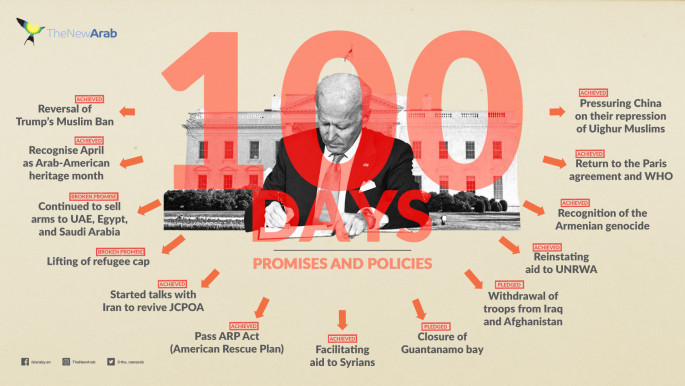

So far, Joe Biden's first hundred days have been characterised by undoing his predecessor Donald Trump's controversial executive orders, trying to fulfil the unmet promises of his former boss Barack Obama, and, in some cases, a combination of the two. Meanwhile, he is trying to forge his own legacy with mass Covid-19 vaccinations, economic relief, and a pending infrastructure bill.

While the pandemic may have stalled some of Biden's more ambitious foreign policy agendas, he has managed to dive into the contentious Iran nuclear deal, restart aid to Palestinians, made plans to facilitate support to Syrians, and has announced plans to end America's so-called forever wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

|

The early days of a presidency can lay the foundation for what is to come, shedding light on a president's strengths and vulnerabilities, as well as what differentiates him from his predecessor |  |

"It's hard to get anything done in the first hundred days, and it's hard to screw anything up either," says Michael Desch, a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame.

Nevertheless, the early days of a presidency can lay the foundation for what is to come, shedding light on a president's strengths and vulnerabilities, as well as what differentiates him from his predecessor.

"When you're running against an incumbent, you have to be against everything the incumbent has done, and you have to look at things differently," says Desch.

|

|

| Read more: Can Biden end America's forever wars? |

He sees the Iran nuclear deal and the withdrawal from Afghanistan as Biden "expend[ing] his political capital" early on. However, these policies could be seen as major feats if successful.

The Iran nuclear deal

The Iran nuclear deal, or the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), was widely considered one of Obama's most successful foreign policy achievements (regardless of whether or not one agrees with the policy, it was arguably no easy task).

Now, Biden is working to re-enter the deal under more difficult circumstances. During the time that has passed since Trump withdrew from the deal, Iran has increased its uranium enrichment, its population has become more mistrustful of the US, and an upcoming presidential election could determine whether or not Iran re-enters the agreement.

"The fact that it's taken so long will make it difficult, if not impossible to revive the deal before the election," says James Devine, associate professor of politics and international relations at Mount Allison University.

"He also has to look at the situation with the Israelis. The Israelis and the Americans are on different pages on this. The message is Israel can't be ignored," says Devine, noting that Saudi Arabia appears to be onboard. He adds, "The bottom line is that he took a long time to get started, and maybe there's not enough time left."

|

Biden's first 100 days have been characterised by undoing Trump's controversial executive orders, trying to fulfil the unmet promises of his former boss Barack Obama, and, in some cases, a combination of the two |  |

Ending forever wars in Afghanistan and Iraq

By withdrawing US forces from Afghanistan and Iraq, Biden would be fulfilling a promise that his predecessors did not keep. Over the last two decades, US presidents have tried and then reversed their decisions on withdrawal from both countries.

Ironically, Trump, with his reduction of US forces in Afghanistan, possibly accelerated what would be inevitable for a future president. In announcing America's withdrawal, Biden made a speech earlier this month in which he maintained that there will never be a perfect moment to leave, but that it is well past time.

"We cannot continue the cycle of extending or expanding our military presence in Afghanistan, hoping to create ideal conditions for the withdrawal, and expecting a different result," he said. "I'm now the fourth United States President to preside over American troop presence in Afghanistan: two Republicans, two Democrats. I will not pass this responsibility on to a fifth."

Gordon Adams, a professor of US foreign policy at American University, sees the withdrawals from Afghanistan and Iraq and the Iran nuclear deal, as policies Biden should have implemented immediately. "I wish he'd done these on day one," says Adams. "Both these and Iran are targets of endless politicising. Now, sadly, we're watching these get politicised."

A symbol of America's post-9/11 endless wars, part of the vague "war on terror", is the Guantanamo Bay detention centre. Though Biden has promised to close it, he has given little indication of how or when he would do so.

|

|

| Click to enlarge |

Human rights abroad

In the area of human rights abroad, Biden appears to be forming a mixed strategy. Large-scale arms sales to the Gulf states continue, amid a humanitarian crisis in Yemen and the still unpunished murder of Washington Post Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, with all indications pointing to the Saudi government as the perpetrator.

On the campaign trail in 2019, Biden told the Council on Foreign Relations, "I would end US support for the disastrous Saudi-led war in Yemen and order a reassessment of our relationship with Saudi Arabia." So far, this does not appear to be happening.

Meanwhile, over the weekend Biden became the first president in US history to keep his campaign promise of recognising the Armenian genocide by Ottoman forces in 1915. It is a symbolic pledge that none of his predecessors had kept out of concern for America's relationship with Turkey.

This move was possibly to open the door for the Biden administration's policy toward China on its treatment of their Uighur minority. In March, the US imposed sanctions on two Chinese officials for its purported abuse of Uighurs, and lawmakers have become increasingly outspoken in advocating for setting conditions on US imports from the Xinjiang province and for the boycott of the Beijing Olympics, with US Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently describing China's policy toward the Uighurs as genocide.

|

Despite the pandemic stalling some more ambitious foreign policy agendas, Biden has managed to dive into the Iran nuclear deal, restart aid to Palestinians, and has announced an end to America's so-called forever wars |  |

Domestic policies

On the domestic front, the Biden administration has broken new ground in recognising April as Arab American Heritage Month, an announcement that was made by the State Department. The month promotes Arab culture, history and the arts for a community that is often demonised or sidelined.

However, on immigration, it appears to have fallen short on its promises of a more humane policy. The US Citizenship Act of 2021 pledged better transparency, an end to family separation, and to embrace diversity.

|

|

| Read more: The Muslim travel ban is over. What happens now? |

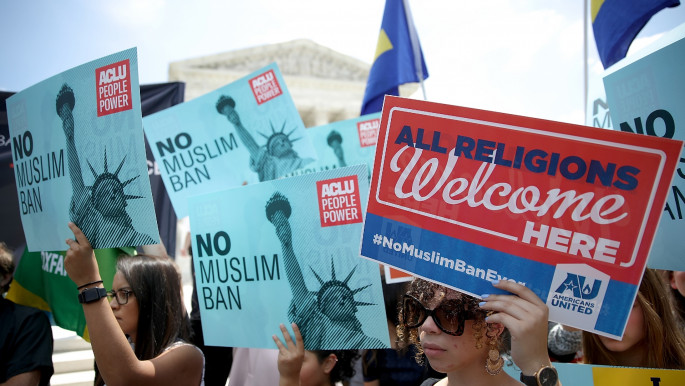

For many immigrants, the bureaucracy of the last four years remains. "What we have seen over the past hundred days, unfortunately, is that the vast majority of our clients have not received their visas," Shabnam Lotfi, an immigration lawyer based in Madison, Wisconsin, told The New Arab. "We've concluded that the rescinding of the Muslim ban has been mainly symbolic."

For example, when her clients are awaiting their green cards, she applies for them to have work authorisation permits. She says under Obama the authorisation took three months, under Trump it took 46 months, and under Biden it takes at least 9 months. One of her clients, a physician, who applied last year, starts her residency in June and has yet to get word on her work authorisation.

"When it comes to immigration and the Middle East, we're still operating as if Trump is still president," say Lotfi, noting that many embassies remain understaffed, a major hindrance for her work. Another important category are refugees, whose numbers were expected to rise significantly under Biden. Instead, the Trump-era historically low cap of 15,000 for the fiscal year remains.

Lotfi sees these broken promises on immigration as a black eye for America. "I don't know if this is intentional or not intentional. Don't make promises you can't keep," says Lotfi. "I think our word is in question. Why give people false hope?"

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News