Arab cartoonists fighting to create their own space

Cartoonists across the Arab and Muslim worlds came out in January in solidarity with their French companions at Charlie Hebdo.

Faced with government censorship in their respective countries, they are questioning the limits European cartoonists impose on themselves and the reasons behind caricatures of the Prophet, either in Europe or in Muslim countries.

There is a broad consensus that under no circumstances should the response to the cartoons be an armed one. The debate is taking shape, now that the initial shock has faded, and we can now begin to discuss the nuances and limits of the freedom of expression and respect for others.

It is a discussion that is as old as attempts in all types of power circles, whether political, religious or social, to establish limits based on their interests or to control the thoughts and channels through which public opinion is formed.

|

While it is true that the cartoon is an essential element of criticism, and that its aim is to make fun of what happens around us, in the Arab world its impact is greater - as it serves as a communication channel for numerous ideas intended to reach an audience that would never read an opinion article or take notice of a political meeting.

The ability to simplify a fact while adding a critical overtone tinged with irony transforms political caricatures into a weapon much feared by ruling institutions.

In addition, the use of different dialects bring the cartoons closer to their publics. It is worth remembering that in the Arab world, TV news broadcasts use only classical Arabic or the language of the coloniser.

On this subject, Khalid Gueddar, a former collaborator with Charlie Hebdo, is categorical: "My cartoons in French (Courrier International and previously, Charlie Hebdo) have less impact than those I do for the Arabic press. The French ones are looked at by an elite audience, whereas the others are generally seen by the people."

Freedom of expression

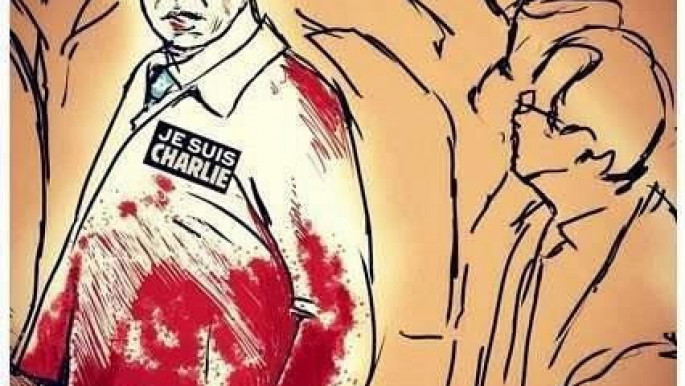

In reality, the discussion over knowing where respect begins and where freedom of expression ends is equally present on the Old Continent.

Even the Pope has taken a position on the issue. In addition to the freedom of expression hardliners - represented by the already popular slogan, "Je suis Charlie" - and those who, to the contrary, do not identify with what the newspaper published, declaring, "Je ne suis pas Charlie", there is the third group in the Arab and Muslim worlds - of those who are opposed to what was published, committed to defending the image of Islam, some of whom have expressed themselves with the hashtag #NiCharlieniKouachinemereprésentent (#Neither CharlieNorKouachiRepresentMe).

In this vein, the initiatives were either personal - using social networks - or the subject of more organised projects, such as that of the Algerian daily Echorouk, on 14 February, in which 12 cartoonists rejected the front cover of the latest issue of Charlie Hebdo, which once again depicted the Prophet.

The Iranian regime went one step further in re-launching the international Holocaust cartoon contest, the first edition of which took place in 2005 when the first caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed appeared.

Aside from the provocative nature of the competition, there is a general consensus in the Arab world about denouncing the "double standard" that decides which subjects fall into the "freedom of the press" category, and which do not.

"In the West, there are no obstacles to publishing material concerning the Prophet, but you don't see anything about Jews or the Holocaust because that would be anti-Semitism," said Mohamed Sabaaneh, a Palestinian who suffered combined reprisals from Israeli authorities and the powers of Hamas and Fatah.

|

Nasser al-Yaafari, cartoonist at the Jordanian daily Al Ghad, asks of Europeans who demand that Arabs caricature prophets and religions as proof of their commitment to freedom of the press, that they "understand, themselves, the limits and conditions which prevail in the Middle East. Traditions are deeply engrained, and religion is very present in our society. For us cartoonists, who are always looking for freedom of expression, it's a very complicated situation."

|

Born of the alternation between "we can draw anything" and "we can't draw subjects that are socially unacceptable" is a debate that usually leans towards the notion of social responsibility.

For the Yemeni Kamal Sharaf, "the cartoonist presents an idea with a critical message that can be understood by all members of society; he tries to sum up the elements of his environment, presenting it in a simple and ironic way, that strikes a chord with his audience and which plays to their imagination".

Discussing subjects that his readers cannot identify with would be completely meaningless. Since his exile to Geneva, Hani Abbas, a Syrian of Palestinian origin and winner of the Cartoons for Peace Prize 2014, has said that the responsibility that many Arab cartoonists speak of begins with a constructive reading of their work.

His co-prize winner, the Egyptian Doaa al-Adel, echoes that.

"You aren't there to shock society, you're there to make it change, to surprise it, but not to cause it to split. Any subject that does not have a positive effect, that doesn't bring anything to that society, doesn't deserve to be drawn. There are so many others that are deserving: hunger, bombings in Gaza, tyranny... why return to a 2,000 year-old subject?"

Caricaturing the Prophet

It is treading this line between surprise and rupture that is leading to increasing problems for a generation of cartoonists, after the Arab revolutions freed cartoonists of the ties that the dictatorial regimes had previously imposed on them and which curbed their creativity.

Despite reduced freedoms over the past few years due to Arab counter-revolutions, it seems that, when it comes to political criticism through caricatures, a return to the previous status quo is not possible.

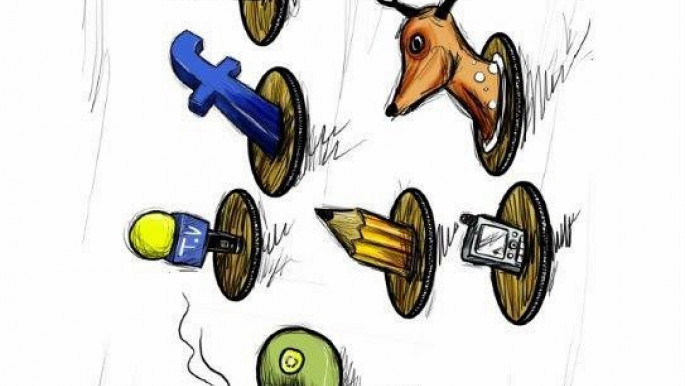

While traditional media, including Egyptian newspapers, are closed to the creativity of young people (in Morocco, despite French colonisation, cartoons are absent from the vast majority of the daily press), these young people take refuge in social networks and on the internet.

The figures speak for themselves: in Morocco there are 5,000,000 Facebook users - compared with 300,000 readers of the printed press. Traditional power seeks to control and suppress the freedom of speech that is expressed in these forms of media, but it is far more difficult than muzzling a handful of newspapers.

|

But the courage to continue publishing and standing up to brutal regimes comes at a very high price, and sometimes even costs lives. This was the case of the Libyan Kais al-Hilali, killed in 2011 after having published caustic caricatures of Muammar Gadaffi, some of which were plastered on the walls of Libyan towns.

Akram Raslan was thrown in prison two years ago and has not been heard from since, and Ali Ferzat, (winner of the Sakharov prize 2013), another Syrian, was savagely beaten.

Despite the regression that happened after the Arab revolutions, there is a well-established group of cartoonists in the Arab world that are committed fighting to expanding their liberated space. As Hani Abbas explains: "When we are able to draw what we like without fearing for our lives, that's when we'll be able to talk about freedom."

|

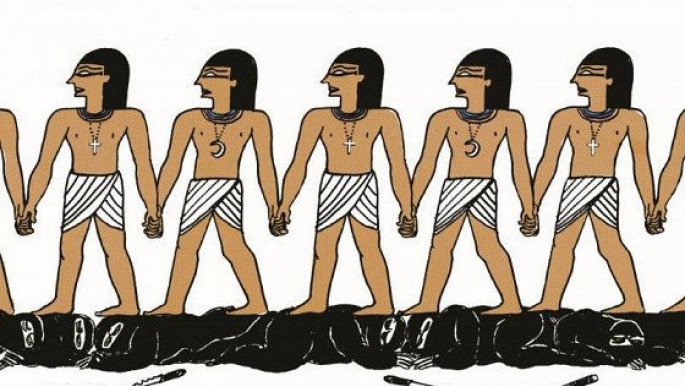

The current priority is not to criticise religion as a belief, rather the partisan use of it made by various Islamic political groups who are looking to protect themselves from political criticism in the name of Islam.

With this in mind, Doaa al-Adel mocked the claims of certain religious figures who assured that those who voted "yes" in the Egyptian constitutional referendum would go to paradise and those who voted "no" would go to hell.

And the crime of Doaa al-Adel? Drawing a parallel with Adam and Eve in paradise, under the apple tree, wondering how they should vote.

Caught in this trap, young Arab cartoonists have taken a clear stance.

"We must not let them intimidate us," said Mohamed Sabaaneh. "We must continue to criticise. In reality this criticism is part of the fight against extremism; in normalising criticism and satire aimed at the political leaders of religious obedience, we bring them down to the level of mortals, we humanise them."

This is an edited translation of an article originally published by our partners at Orient XXI.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News