With Washington completing 95 per cent of its troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Taliban's opportunistic offensive has left the country now facing what Kabul's national security adviser called an "existential crisis" in a briefing to journalists in London last week.

The Taliban now control an arc of territory from the border region with China all the way to Iran, surprising analysts by consolidating power over a region of the country once the heartland of the anti-Taliban resistance.

Key supply lines from the capital to the country’s north and east have been cut, while the insurgents rake in lucrative custom duties from border crossings under their control.

The situation is the same in southern Afghanistan, where local militias are fighting alongside beleaguered government forces to cede back control of the provinces of Kandahar, Ghazni and Helmand.

Yet amid the insurgent onslaught, eastern Afghanistan appears to be an outlier.

"The Taliban now control an arc of territory from the border region with China all the way to Iran, surprising analysts by consolidating power over a region of the country once the heartland of the anti-Taliban resistance"

As international media outlets rush to produce maps depicting the Taliban's massive grip on the country, it has struck many observers that district centres in the provinces of Nangarhar, Laghman, and Kunar are not yet falling into Taliban hands, at least not on the same scale as elsewhere.

Known as the Mashreq, those three provinces along with Nuristan are bound by common eastern Pashtun linguistic and cultural ties – a reality that plays in the favour of the local Taliban, whose presence is entrenched in some districts and mountainous regions.

Kunar has been known for providing hiding places for an array of militant groups, including the Taliban, who helped its winding valleys earn the reputation for being the most mythically dangerous area for US forces anywhere in the world.

But the defeat of Afghanistan's Islamic State (IS) affiliate, known as Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), first in their de facto capital Nangarhar in 2019 and then a year later in Kunar, saw the rise of a major challenge to Taliban dominance - local uprising forces.

|

|

A July war report published by the Afghan Analysts Network (AAN) notes that in the Mashreq, "where Taliban have attacked government positions, they have achieved little. So far, the ANSF [Afghan National Security Forces], along with Uprising Forces, have defended their positions successfully".

Nabiullah Baz, a member of parliament representing the Nangarhar district of Chapliyar, said the success of local resistance against ISKP, and now possibly the Taliban, is due to the fact that it is a grassroots uprising, free from the leadership of corrupt former warlords with ethnic or factional interests.

"There is no single figure representing the people of the Mashreq, unlike other regions of Afghanistan, where you have warlords such as Atta Noor, Ismail Khan and General Dostum mobilising their militias in the fight against the Taliban," the 28-year-old lawmaker told The New Arab.

"In Nangarhar it will be a local-led effort by people who refuse to be ruled by brutal fundamentalists."

But how much local morale will drive efforts to fend off any future Taliban offensive is unclear. Speaking to TNA, Ali Latifi, an Afghanistan-based journalist, said that local militias never received adequate recognition for their role when they drove out ISKP from the province.

Instead, following the disintegration of the local police, locals had been marginalised and disillusioned by harsh treatment from national police forces brought in from other provinces in Afghanistan.

Dr Hamdullah Mohib, Afghanistan’s National Security Advisor, hails from Nangarhar.

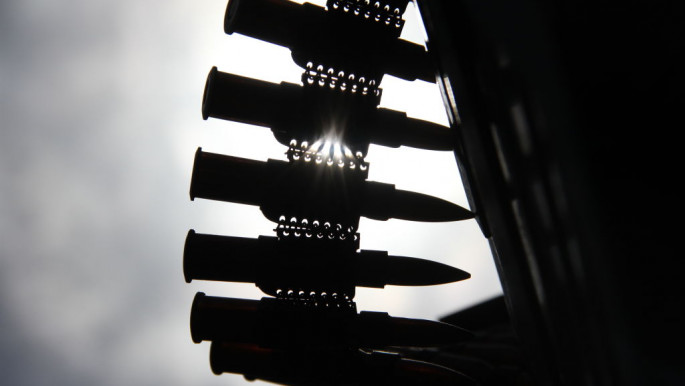

Last week, he expressed reservations about funnelling arms to locals, saying it was something his government was monitoring. Rivalries between armed militias sustained the country’s brutal civil war between 1992 and 1996.

"The success of local resistance against the Islamic State affiliate, and now possibly the Taliban, is due to the fact that it is a grassroots uprising, free from the leadership of corrupt former warlords with ethnic or factional interests"

Dr Mohib told The New Arab that the Mashreqi provinces were some of the "biggest contributors" to the Afghan National Security Forces and that this deterred the Taliban from expanding their grip on the region.

Mid-level commanders in Laghman province are believed to have been instrumental in protecting outposts effectively under siege by the Taliban. But two of Laghman’s five districts are now in Taliban control, with the insurgents having used village elders, who sometimes strongly sympathise with the Taliban, to negotiate surrenders.

Even during a month-long truce between the government and Taliban in the Laghman district of Alingar, the insurgents were able to shift resources to the neighbouring district of Alishing, where they were able to negotiate surrenders, and ultimately, the fall of the district.

Dr Mohib was in London days after standing on the same row of worshippers as Afghan President Ashraf Ghani, when the presidential palace was rattled by three rockets during Eid prayers. The attack was claimed by the Islamic State group.

|

|

While President Ghani declared victory over ISKP in 2019, a UN report released that year acknowledged the role of both the Taliban and Afghan security forces in inflicting damage on ISKP and displacing it from large areas of Nangarhar.

In Kunar, ISKP's defeat saw cooperation between Afghan government forces, local uprising forces, the Taliban and the US.

In addition to the Doha deal between Washington and the Taliban, that alliance was made possible in part due to a deal between the provincial government and the Taliban shadow administration in the province.

"In Nangarhar it will be a local-led effort by people who refuse to be ruled by brutal fundamentalists"

An Afghan Analyst’s Network report in March found that the latter alliance had not strengthened the government's position in Kunar, as it had been unable to retake territory following ISKP’s defeat.

"The risky hidden deal that they forged with the Taliban put them on the back foot, offering the Taliban an opportunity to claim the victory, as well as to take larger areas under their control," the report said.

Over the weekend, media reports emerged stating that two of Kunar’s districts – Ghaziabad and Narai - had fallen to the Taliban.

Among the eastern provinces, only Nangarhar was excluded from a countrywide night-time curfew announced on Monday to stem the Taliban advance.

How long Afghanistan’s Mashreq will remain an outlier in the country's war remains to be seen.

Kamal Afzali is a journalist at The New Arab.

Follow him on Twitter at @KNIAfzali

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News