Israel to allow graves of 'stolen babies' to be opened

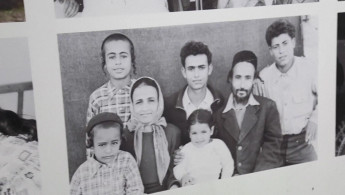

Activists and family members believe up to several thousand babies were taken in the years after Israel gained statehood in 1948, mainly from Jewish Yemenite families, but also from immigrants of other Arab and Balkan nations.

Official investigations have found that most of the missing babies had died, pointing out the poor conditions in reception camps for immigrants.

Many families have not been convinced and have pushed for the graves supposedly holding the remains to be opened.

Israeli prosecutors have now agreed to a request from 17 families hoping for DNA tests on the remains to determine if there is a genetic link, the justice ministry said.

Since a wave of Yemenite Jewish emigration to the newly created state of Israel in around 1950, Yemenite activists have charged that hundreds of babies declared dead by doctors were actually abducted for adoption by European Jewish couples.

They say the babies went missing from camps set up to host Yemenites and Jews arriving from other Arab countries in the early 1950s.

Doctors at the camps told them their children had died, but refused to hand over bodies or death certificates, according to the families.

In 2016, Israel's national archive announced the launch of an online database of 200,000 documents aimed at putting to rest the decades-old allegations.

The Amram NGO, which has worked on the case, was sceptical that the DNA tests would reveal the truth.

"This is a very complicated case and we think that the government has to recognise that a crime was committed (in order) to make progress," Amram's Naama Katihi told Israeli paper Maariv.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

![Israeli forces ordered bombed Gaza's Jabalia, ordering residents to leave [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_330x185/public/2176418030.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=_YGZaP1z)