To protect and punish: Can Caesar Act sanctions avoid harming Syrians, too?

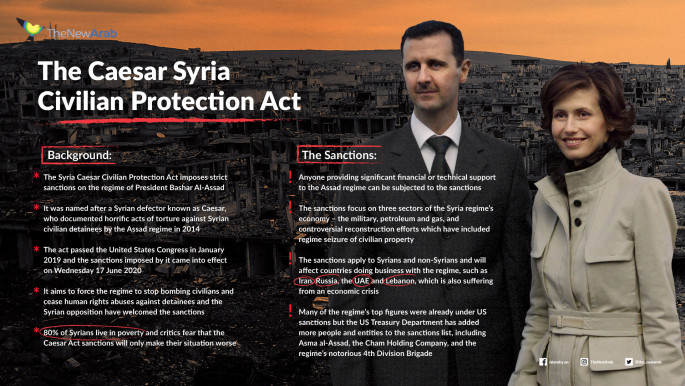

The Caesar Act was passed by the US Senate in 2019, with the stated goal of more targeted and severe sanctions against regime apparatuses, businesses, individuals and foreign supporters of the Assad regime. Any person, institution or business that aids Assad's war crimes against Syrians can now be targeted with far-reaching sanctions, including travel bans, asset confiscation and arrest.

The Act is named after the 'Caesar' pseudonym taken by the famous regime defector who leaked 55,000 images documenting the industrial torture and mass murder of thousands of detainees by Assad.

There is clearly no question that the goals of the Caesar Act are righteous, and that the need for this kind of action is pressing, but there are other considerations regarding the consequences - intended or otherwise - of the act, that simply cannot be ignored.

Syria's economy is collapsing. The Syrian lira has crashed 70 percent since April, working out at around 3,000 to the dollar. For the average Syrian living Assad's rump state, a month's salary is about enough to buy one watermelon.

| Read more on the Caesar Act: What is the Caesar Act and how will it impact Syria? |

Contrary to those apologists who blame the previous moderate US-EU sanctions, Assad has brought Damascus to the brink. He has inflicted gargantuan financial toll through waging a relentless nine-year war against the Syrian opposition. The domestic economy has been looted by corrupt loyalist kleptocrats, and relies disproportionately on underwriting from Iran and Russia.

|

It's hard to see a situation where deep economic sanctions won't lead to a bolstering of this grim status quo |  |

Add to this already explosive mix the economic devastation caused by Covid-19, and the Caesar Act in full effect could very well be a cliff edge not just for Assad, but for Syrians, too. In particular, it could impact those in Idlib, which, under the constant threat of Assad and Russia's indiscriminate bombing campaigns, is one of the most precarious places on earth.

History is full of examples of economic sanctions whose outcomes were contrary and cruel regardless of any perceived noble intentions. Economic and political factors often muddy the ethical waters from which they initially emerged.

Preventing the vast, continued suffering Syrians at the hands of Assad and his backers is the stated noble intention of the Caesar Act, but what of the half of all Syrians who currently face food scarcity? It's true that the act provides an exemption for humanitarian supplies, but the aid supply to Syria is complex and hugely determined by Assad's weaponization.

Twitter Post

|

The Caesar Act offers no nuance for the central problem of the fact that even where food is in abundance in Syria, Syrians simply can't afford to buy it; in fact, it could potentially exacerbate these conditions of precarity.

Moreover, Assad's skeleton state - stripped down to the bare bones for the purposes of waging total war and maintaining the worsening kleptocracy - is barely functioning for Syrians as it is. Only the murderous security forces flourish.

Russia, Iran and corrupt loyalist war profiteers pick the bones of Syria's dwindling resources, while ordinary Syrians are economically victimised. It's hard to see a situation where deep economic sanctions won't lead to a bolstering of this grim status quo.

And perhaps this is the central problem with the Act. They say timing is everything and this Act perhaps would have better served the Syria of 2013 than the Syria of today - a Syria that wasn't on the precipice of general and far-reaching economic collapse, but rather one where the regime and its backers could be targeted more easily by these forms of sanctions without the same potential for extreme collateral damage.

But these are all hypotheticals; the war crimes being carried out by Assad are not. And, with Russian strikes on Idlib flaring up again and Assad wasting precious resources on procuring MIG-29 fighter jets and other weapons of war, it is important to remember that no Syrian would be in any of these monstrously precarious circumstances if not for Assad.

This is certainly a point well understood in Suweidah. Over a week ago, anti-regime protests erupted in the Druze-majority province. While the crushing economic crisis grips Syria, the protesters have expressed solidarity with people of liberated Idlib, as well as expressing support for the late popular rebel fighter and anti-Assad activist, Abdul Baset al-Sarout.

|

The Caesar Act is a step forward in that it recognises that Assad is the root cause of every moment of chaos in Syria |  |

The protests seem to be growing, and solidarity demonstrations have taken place in Daraa and Deir az-Zour, with the protesters raising a banner reading "The spring of As-Suweidah is coming with flowers of freedom", and chants calling for the fall of the regime, the expulsion of Iranian forces and an end to corruption.

There is no doubt that these protests demonstrate the fact that the Assad regime is far from secure. Only with the might of Russia and Iran has Assad achieved military victory over the rebels, but while his legitimacy cannot be salvaged, there are few actors capable of uniting and capitalising on this lack of legitimacy.

The Caesar Act could conceivably lead to the collapse of his regime, or, as is the stated aim, force him into a democratic transition. But it could also have the contrary effect of making the regime lash out and dig in with even more brutality in the face of economic assault, while its backers, particularly Russia, could ramp up its brutal intervention to bolster his position. Saving Assad has been a major investment for Russia, it's unlikely that they're going to easily abandon this endeavour.

The current opposition to Assad's regime is either trapped in Idlib, where its own national legitimacy is undermined by the presence of the al-Qaeda-affiliated HTS, or confined to sporadic regional protests, such as those in Sueweidah. Again, like the complicated current economic context, the political circumstances of Syria 2020 are perhaps not best served by the Caesar Act.

|

The political circumstances of Syria 2020 are perhaps not best served by the Caesar Act |  |

The primary focus of the world ought to be in ensuring that the people of Idlib remain safe from Assad and Russia's brutality. Earlier this year, Turkey essentially issued a rallying cry for the world to do so, but, as has been the case for nine years, it fell on deaf ears.

The spirit of the Caesar Act is therefore of huge importance in the sense that it acknowledges that action must be taken to protect Syrians from Assad, but the manifestation of this action doesn't address the current complexities of Syria.

As is the case with the UN only this year conceding that Assad carried out chemical atrocities, the Caesar Act is a step forward in that it recognises that Assad is the root cause of every moment of chaos in Syria - the Syrian genocide remains an open sore on the face of the earth, with its toxicity spreading far beyond its borders.

There's no doubt that his regime must be addressed. But the devil is not just in Damascus, but also in the details. The situation is not as black and white as it once was.

It's possible the Caesar Act has come too late to be truly effective and, worryingly, its consequences could lead to the disastrous outcome of Assad's position being sustained, while Syrians are pushed into new levels of suffering.

Sam Hamad is an independent Scottish-Egyptian activist and writer.

Join the conversation @The_NewArab

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News