The UAE has it in for the Muslim Brotherhood

Among the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Saudi Arabia and Qatar have received the most media attention in recent years.

In France, presidents Nicolas Sarkozy and Francois Hollande have greatly contributed to this, the latter's focus on Saudi Arabia having abruptly replaced his predecessor's passion for Qatar. The same holds for the civil war in Syria, where Riyadh and Doha have been conspicuously supporting the revolt against Bashar Al-Assad's regime.

By comparison, the federation of the United Arab Emirates has kept a low profile. Less populated and less hegemonic than Saudi Arabia, more discreet than Qatar, it has been no less active, especially since 2011.

Abu Dhabi's foreign policy has two principle goals: To protect itself against Iran, and to destroy political Islam in all its forms, with the Muslim Brotherhood as its main target.

While the fear of Iran is shared on the whole by the other Gulf monarchies, the same cannot be said of political Islam, a subject on which the Emirates are completely at odds with Qatar and also - though only recently - with Saudi Arabia.

While King Abdallah of Saudi Arabia was ferociously opposed to the Brotherhood, which he had listed as a terrorist organisation, his successor, King Salman, has tempered that hostility - in order to promote a 'Sunni front', ostensibly against terrorism though actually directed against Iran.

|

Abu Dhabi's foreign policy has two principle goals: To protect itself against Iran, and to destroy political Islam in all its forms, with the Muslim Brotherhood as its main target |  |

Evolving Saudi behavior towards the Brotherhood based on changing political interests resembles Bahrain's, where a Sunni monarchy must deal with a majority Shia population. It also bears some similarity to Kuwait, where the parliamentary system is historically more liberal, despite being a monarchy.

For Abu Dhabi, on the other hand, such a compromise is out of the question: The once well-tolerated Brotherhood gained considerable influence, even at state level in the Emirates. But after the turn of the century, it came to be considered as a threat to national stability, and since 2011 was subject to merciless repression.

Attachment to the Sisi regime

Both Abu Dhabi and Riyadh were strong supporters of President Sisi's coup that ousted President Mohammed Morsi, of the Muslim Brotherhood. The winner of the first truly democratic election ever held in Egypt, Morsi had enjoyed the support of Qatar and Turkey.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

But neither of those capitals were about to allow the Brotherhood to take over an emblematically Sunni country; the most populous in the Arab world, home of Al-Azhar university, and key to strategic depth regarding Iran.

The Emiratis' attachment to the Sisi regime has kept them from getting involved in the conflict between Cairo and Riyadh which has developed in recent months.

This conflict has multiple aspects: President Sisi's public endorsement of Assad, Egypt's refusal to provide ground troops in Yemen to fight the Houthi rebellion, the conspicuous rapprochement between Moscow and Cairo.

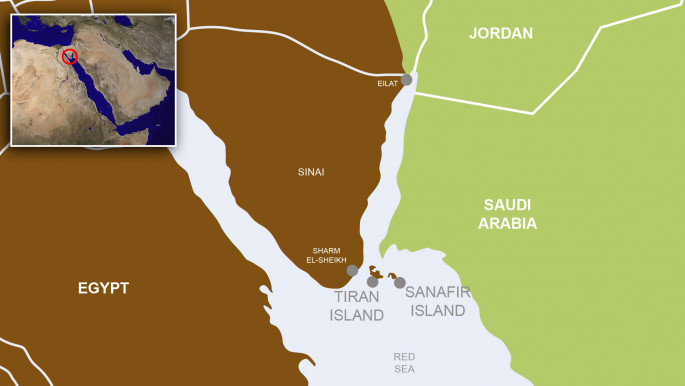

In addition, there is the fact that the Egyptian courts have blocked the transfer to Saudi Arabia of the two Egyptian islands which control the southern entrance to the Gulf of Aqaba - Tiran and Sanafir.

| Read more: Turbulent times for Saudi-Egyptian relations | |

Unlike Riyadh which has, by way of reprisal, suspended its aid and notably its oil deliveries to Egypt, Abu Dhabi still supports Cairo, even while criticising the poor management of the billions of dollars the Gulf countries have poured into Egypt.

Against Ennahdha in Tunisia

Conversely, the UAE has cut off supplies to Tunisia, a country that prior to 2011 was its second largest trade partner, after Libya. Why? Because the government was taken over by the Ennahdha party, affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood.

|

The UAE has cut off supplies to Tunisia, a country that prior to 2011 was its second largest trade partner |  |

This Emirati ostracism persists because of the party's continued presence, albeit with a single minister, in the cabinet formed by President Beji Caid Essebsi. The scenario which Abu Dhabi favoured - the total eviction of the Brotherhood from the avenues of power, like in Egypt during the summer of 2013 - did not come to pass.

By giving up the post of prime minister in January 2014, the Ennahdha leader, partly influenced by events in Egypt, was able to avoid a similar situation.

Tellingly, a forum to discuss stepping up investment in fragile Tunisia was sponsored in large part by Qatar. No representative of the UAE bothered to come, and only two people from a Dubai investment firm were present. By way of contrast, King Salman's Arabia has strengthened its ties with Tunis after a period of extreme tension following the events of 2011.

At odds with Riyadh in Yemen

In Yemen, the Emirates are part of the military coalition formed by Saudi Arabia in 2015 to combat the Houthi movement which has rebelled against the regime of President Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi.

Despite this, they do not approve of Saudi support for Al-Islah, the Muslim Brotherhood's party in Yemen, whose tribal militia are nonetheless fighting side by side with the troops loyal to President Hadi.

Similarly, the two monarchies disagree about the nature of the future Yemeni regime and the identity of its future leaders. Both deny the existence of any disagreement, but in reality, the role - if any - to be granted to the Muslim Brotherhood in Yemen, is a deep source of division.

Abu Dhabi also criticises Riyadh's lack of concern over the expansion of jihadi groups in Yemen, profiting from the present chaos.

| Read more: Two years of all-out lawlessness plagues Yemen | |

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) has gained considerable territory in the southeastern and eastern parts of the country. Even IS, absent from Yemen until the intervention of the Saudi-led coalition, has appeared as the result of a schism within AQAP. In fact, for a long time, the Saudis avoided bombing AQAP, which was fighting the Houthis.

For its part, IS perpetrated murderous attacks against both the loyalists, notably in Aden, and the partisans of Ansrullah, including in Sanaa itself. Consequently the Emirates, while still formally part of the Saudi coalition, have concentrated their war efforts on jihadi organisations.

They are now taking part in the campaign the US have waged against AQAP for many years now, primarily via drones, but also by special forces commando operations. As a result, in January, Emirati soldiers took part in the first US special forces raid under the Trump presidency on a safe house for Al-Qaeda fighters.

Damascus road

While backing the moderate opposition to the Assad regime, the Emirates, unlike Qatar and Saudi Arabia, have been careful to avoid supporting any Islamists. With increasing numbers of Islamists in armed groups, they advocate a political solution, involving the Russians and Americans.

Although not going so far as to openly adopt the Egyptian position - favourable to Assad, Abu Dhabi's behaviour towards Damascus is now less aggressive than previously.

Along with their American counterparts, Emirati special forces are said to be training elements of the opposition. They constitute a kind of Arab guarantee among the Syrian Democratic Forces - an umbrella group dominated by the Kurds of the PYD, on whom the US are relying to fight IS on the ground.

The UAE is also participating - with its F16s - in the US-led anti-IS coalition. Their actions are however confined to the Syrian theatre, like the other Arab members of the coalition, among which the UAE is nonetheless proving to be the most active.

Military support to the Libyan opposition

In Libya, the Emirates' role is particularly conspicuous for they find themselves in direct armed confrontation with Qatar. Their involvement here goes back to 2011, when with the technical assistance of the US, their F16s participated in the NATO operations to bring down Gaddafi's regime.

From then on, Emirati special forces fought side by side with non-Islamic militias. Doha, besides the contribution of its Mirage 2000s to the anti-Gaddafi coalition, with the technical backup of France, also sent its special forces into Libya but this was for the benefit of an Islamist militia.

|

In Libya, the Emirates' role is particularly conspicuous for they find themselves in direct armed confrontation with Qatar |  |

These rival interventions, both carried out with the blessing of France - reluctant to alienate either of these two important trade partners - only deepened the state of chaos. Since then, the Emiratis have allied with Egypt to provide military support to General Haftar who opposes the shaky government in Tripoli, that was set up with the help of the international community.

Since 2014, Haftar has commanded a self-proclaimed national army attached to the Tobruk parliament in exile. They are fighting every manifestation of political Islam in general, and the Muslim Brotherhood in particular. The General even describes the Brotherhood using rhetoric lifted from President Sisi's, referring to them as a "terrorist group"; no different from the jihadi groups tied to Al-Qaeda or IS, also present in Libya.

Thus the Emiratis find themselves in military opposition to the Qataris, who are backing and arming militia close to the Brotherhood, especially those operating in Misrata.

|

On the Palestinian question too, the fight against the Brotherhood determines Abu Dhabi's attitude |  |

These made up the bulk of forces allied with the Tripoli government which, with the support of the US air-force, drove IS out of Sirte in 2016. Abu Dhabi went so far as to bomb Islamist militias in Tripoli using aircraft based in Egypt.

More recently the Emirates have provided General Haftar with light propellor-driven planes for ferrying ground-troops. The pilots were mercenaries supplied by the former head of the now defunct Blackwater company, Erik Prince, who has been doing business with Abu Dhabi for several years.

In Libya, while the UN is struggling to sustain a compromise government in Tripoli, the Emirates are supporting its most powerful adversary, in the name of their struggle against any and every form of Islamism.

Dahlan, Haftar and Russia

On the Palestinian question too, the fight against the Brotherhood determines Abu Dhabi's attitude. Not content with giving refuge since 2011 to Mohammed Dahlan, they hope to see him become Mahmoud Abbas' successor, despite opposition inside Fatah, where he is accused of corruption and of having had a hand in the supposed poisoning of Yasser Arafat.

Dahlan is a fierce enemy of the Brotherhood, and Hamas in particular, as well as being on the best of terms with Israel and Egypt.

|

Of all the monarchies in the GCC, the UAE undoubtedly has the best relations with Russia, while remaining a very close ally of the United States |  |

Of all the monarchies in the GCC, the UAE undoubtedly has the best relations with Russia, while remaining a very close ally of the United States. We encounter this proximity in Libya, where Moscow, while posing as a mediator, is nonetheless supporting General Haftar, who made a visit to Moscow in 2016 and was invited on board the aircraft-carrier Kouznetsov off the Libyan coast in January 2017.

The same is true in Egypt, where Russia has been increasingly present, especially in military matters since Sisi took power. This proximity even exists in Syria, at least to some extent, as Abu Dhabi argues in favor of a partnership with Russia.

Weakening political Islam by any means

This proximity was also on display in Abu Dhabi's involvement in organising a conference on Sunnism in Grozny at the end of August 2016, in collaboration with Chechen president, Ramzan Kadyrov.

The event hosted a particularly large Egyptian delegation, led by the Grand Immam of Al-Azhar. During it, Wahhabism (the Saudi brand of Salafism) was declared a dangerous distortion of Sunni Islam and not even a part of it.

|

The United Arab Emirates banks on eliminating the Brotherhood within its borders and combating it everywhere else |  |

However, the final press-release made no mention of either Saudi Arabia or Qatar, countries which had not been invited and where Wahhabism is the official doctrine.

By supporting the ostracisation of the brand of Salafism propagated by Saudi Arabia, the Emirates was hoping to reiterate their opposition to any form of Islam likely to further the growth of jihadism.

This political and religious attack on Riyadh is a direct challenge to the Saudi monarchy's claim to hegemony over the Sunni population of the world. Saudi Arabia's violent verbal reaction was mostly aimed at Egypt, further entrenching the feud between the two countries.

Their reaction did however spare the Emirates who had not been officially involved in setting up the conference, except by way of a foundation based in Abu Dhabi.

The United Arab Emirates banks on eliminating the Brotherhood within its borders and combating it everywhere else. For them it is important to weaken the networks of a political Islam which they still fear might rear its head again within the Federation, where its sympathizers - though now forced underground - have not disappeared.

Marc Cher-Leparrain is a former French senior official whose career has been devoted to the Middle East, where he also held diplomatic positions. He is currently a member of the editorial board of Orient XXI online magazine.

Follow him on Twitter: @Mcleparrain

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News