The crisis of political Islam (II): Islamism and politics

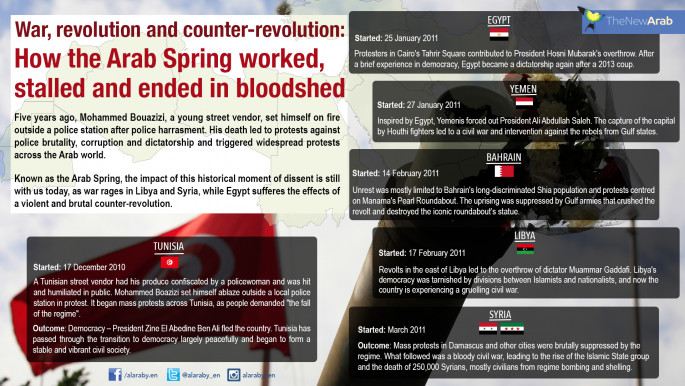

The Arab revolutions of 2011 and the subsequent failure of democratic transitions in some of the countries that witnessed them exposed the shallow, if not non-existent democratic culture among Arab political elites, both Islamists and non-Islamists.

Vis-à-vis the revolutions, the ruling elites were unwilling to compromise, showing no hesitation in staging massacres or even destroying entire countries in the cases of Syria and Libya, to remain in power.

But for their part, the elites that were in the various opposition movements saw the revolutions as an opportunity to rise to power.

The opposition elites did not understand or want to understand that the goals of any revolution against tyranny, including freedom, justice and dignity, can be relatively ensured only by democratic systems, and that building such systems was the requirement that followed toppling tyrannical regimes.

Therefore, in order to take power, these oppositionists were all too willing to seek elections before consolidating democracy - in the case of the Islamists - or to ally themselves to the remnants of the ancient regimes against Islamists, in the case of self-styled secularists.

In other words, they picked and chose what suited them from the revolutions, while disregarding democratic principles that the protesters had advocated during civil uprisings and for whose sake the youth had made many sacrifices.

Read Part I:

The crisis of political Islam: Problems of terminology |

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

The responsibility for the deterioration of conditions that followed, therefore, lies with both the ruling echelons that held on to power at any cost, and the narrow-mindedness of the organised opposition forces that took over after the squared became empty.

The goal of the masses that rose up was to topple tyranny and achieve freedom and dignity, which can only be guaranteed by a democratic constitution.

Save for some rare exceptions, the Islamist movements tried to avoid having an unequivocal commitment to democratic principles, save for championing rule by majority as expressed in ballot boxes.

The truth of the matter, however, is that democracy comes ahead of elections as a mechanism of governance, not vice versa.

Outside the framework of a democratic system agreed upon by all, elections in and of themselves could lead to democracy but could also lead to chaos and forms of dictatorship.

|

After the Arab revolutions, Islamists failed to understand the need to forge alliances with other political forces on the basis of democratic principles |  |

Democratic failure

After the Arab revolutions, Islamists failed to understand the need to forge alliances with other political forces on the basis of democratic principles, in order to ensure national unity against the ancient regime.

They caved to the one-upmanship of other more hard-line Islamists, fearing they would steal their electoral support.

Having chosen only elections from the broad notion of democracy, the Islamists failed to persuade society of their honest intentions regarding civil liberties, without which no modern democracy could possibly function.

There were two reasons for this. First, the Islamists were not convinced enough of the importance of freedoms for people in our modern era, including personal freedoms. They falsely thought this was an issue of concern only for the upper middle classes.

Secondly, they underestimated the clout of those concerned by personal freedoms and the clout of the middle class itself in urban settings and state institutions, where the middle class punches above its relative weight in the population.

The Islamists believed people only cared about identity issues and daily livelihoods, and still mismanaged the latter issue since they lacked a particular vision on that count.

In the absence of a particular vision in this regard, national unity at the very least should have been sought to tackle socio-economic crises, corruption and the forces that control the economy and that usually resist change. But this did not happen.

|

The Islamists behaved like a religious sect rather than a political party |  |

Cult, not political party

On top of all of this, the Islamists failed to understand how modern states work, and the nature of their bureaucratic apparatuses, power centres and the various interests lurking therein.

The Islamists behaved like a religious sect rather than a political party, though some extremist non-religious ideological parties act in the same way.

Under tyrannical rule, the Islamists lived as a cohesive unit based on solidarity among its members who sought support from a particular pattern of religiosity to withstand their ordeals.

This partisanship, combined with religious symbols, the movement's many martyrs, and a collective memory of plight, persecution and victimhood led the Islamists often to behave like a cult rather than a political party that people can join or leave based on how persuasive its platforms are.

Indeed, entire generations were born into the Muslim Brotherhood like generations were born into a religion. In overt political action, this raises the possibility of dividing the world between adherents and the rest of people, because there is a solid basis for it.

In reality, this weakness is exactly what the ancient regime has exploited to stigmatize them isolate them from the remainder of society.

If we add to this closed structure the Islamists' claim of possessing absolute religious truth, we will understand just how difficult it is for them to build alliances on the basis of specific joint objectives.

|

The mistrust of all those who are non-Islamists could easily be exploited among some naïve Islamists by any impostor claiming to be religious |  |

Opportunistic alliances

To be sure, every alliance they seek is instead just a means to an end, the end being fulfilling their own objectives, and soon, the allies will feel they are mere tools to be discarded at the first juncture.

Closed ideological movements [both secular and religious] rarely show solidarity with allies in their ordeals, yet ask everyone else for solidarity. They accuse former allies often of apostasy, opportunism and treachery at the first sign of disagreement: to them, one is either with them, meaning subservient to them, or against them.

On the other hand, the mistrust of all those who are non-Islamists could easily be exploited among some naïve Islamists by any impostor claiming to be religious. This makes it easy to infiltrate Islamist groups and steer it politically using non-political means.

One of the weaknesses of religious political movements is accepting anyone superficially religious, even if it were a bad person, and rejecting competent and virtuous people should they be non-religious.

Without understanding this issue that stems from the movement's ethos, rather than bad intentions, one cannot understand how the elected Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi was fooled by a person like Maj. Gen. Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, the fiercely opportunistic chief of military intelligence who pretended to be pious and docile, and nominated him his Minister of defence.

Such non-political and unprofessional considerations that undermine politics, are also often the benchmark for appointments made by Islamists.

It is possible to list many factors that allowed the forces of the ancient regimes to forge alliances with non-Islamist opposition forces against Islamists. But the above remains true nonetheless.

|

It is impossible for religious forces to return to the political process without making a clear commitment to the principles of democratic systems in an unequivocal manner |  |

Persuasion behind bars

The democratic program supported by the majority of people was abandoned, and the youths of the revolutions were side-lined, despite being the generation that will rule the Arab countries in the future.

The author had a firm conviction the participation of the Islamists in the democratic political process was a necessary condition for success political transition. Participation would have also helped them move away from their culture of opposition to a position of responsibility for states and societies, and also to adopt the tenets of democratic culture.

The forces of the counter-revolution abolished this precious opportunity by excluding, persecuting and oppressing Islamists, exacerbating social and political polarization that is closer to being a civil war than to pluralism.

Yet today, it is impossible for religious forces to return to the political process without making a clear commitment to the principles of democratic systems in an unequivocal manner, one that would not partition citizenship on religious basis.

However, on the other hand, it is difficult to preach to people to adopt democratic principles when they are behind bars, or being oppressed, persecuted and demonised by a military dictatorship.

The failure of Islamist movements in the transitional phase in Egypt, which was deliberately thwarted to boot, corroborates the conclusions reached by the Tunisian Ennahdha movement that followed a different evolution.

Ennahdha was open to the broadest possible alliances to preserve societal stability and avoid polarisation and civil war, and to preserve democratic transition from a potential military coup.

Openness and reform, all the way to separating religious preaching from civil political action, were the conclusions reached by other Islamists from the new generation.

But the crucible and violence of the counter-revolution, the persecution and torture in prisons, and most importantly, the feeling of having been betrayed by the "ruse" of democracy, with the failure to respect the choices of the electoral majority, are all not a favourable climate conducive to cementing such conclusions.

Meanwhile, some of the new-generation Islamists slipped into the path of violence, the subject of the next part in the series.

Azmi Bishara is a Palestinian intellectual, academic and writer.

This article is part two of five in a series on political Islam. Read part one here.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News