99 Years after Balfour, awaiting the Obama Declaration

Nearly a century ago this month, the imperial British government issued a position that would to this day shape the Middle East.

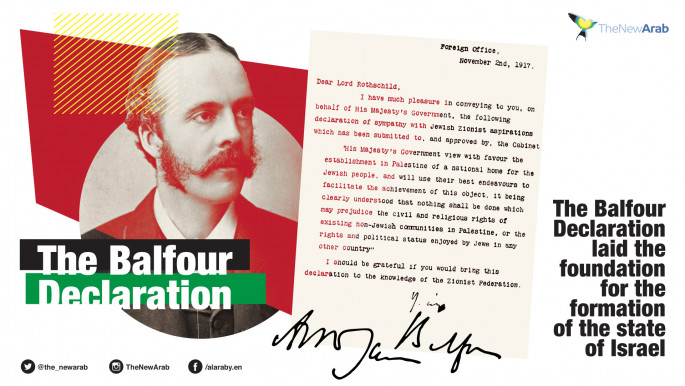

The Balfour Declaration, a communication sent by then Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour for transmission to Zionist leaders, noted the support of the imperial government to establish "in Palestine a national home for the Jewish people".

At the time of the writing, Palestine was still under Ottoman rule and the British Mandate would not even begin for another few years. The population of Palestine at the time was 87 percent Arab.

Britain was undoubtedly aware of the conflict it would stir through the support it lent for the Jewish colonisation of Palestine. Yet, nearly a century later, here we stand looking back at this moment as a seminal one in the morass we witness between the river and the sea today.

But the lessons of the dangers of the Balfour declaration seem to have gone unlearned. Britain at the time was responding to lobbying by Zionist interests and also hoping to appeal to Jewish constituencies in allied countries in a bid to galvanise Jewish support for the war effort.

Though the land of Palestine was overwhelmingly populated by Arabs who were seeking independence and not to live under a Jewish state, and while Britain did not even control the land at the time, the declaration was instrumental for the Zionist movement to point to in the effort to create an international consensus around the legitimacy of their colonisation efforts.

The declaration issued in 1917 came 20 years after the first Zionist congress in Basel. During these two decades, Jewish immigration into Palestine led to a doubling in the Jewish population both in absolute numbers (from ~50,000 to ~100,000) and as a percentage of the population (from ~8 percent to ~15 percent).

|

The message that Zionists took from this is that if they could grab it, the world - or at least the powers that have most sway in it - would eventually recognise it as theirs |  |

As the Zionists were able to create more facts on the ground, laying claim to territory through populating it with European Jewish immigrants, they sought international recognition of their efforts.

This is a process that would repeat over stages. By 1947, despite still being a minority (32 percent) in comparison with the native Arab population, the Zionists were able to garner an achievement in the form of UN General Assembly resolution 181 which apportioned to a Jewish state the majority of the territory (55 percent).

Taking this legitimation of their efforts as a green light, the Zionists continued to build on the footholds they created in Palestine and after Israeli conquest operations during the 1948 war, a Jewish state was established not on 55 percent of the land but on 78 percent of it.

|

|

| Click to enlarge |

Subsequent international recognition of the new Israeli state lent legitimacy to this furthest and then most recent expanse of the Zionist settler-colonial project.

The message that Zionists took from this is that if they could grab it, the world - or at least the powers that have most sway in it - would eventually recognise it as theirs.

The next stage of this expansionist effort was treated differently, however, when the international community viewed Israel's occupation of further Arab territory as the unjust acquisition of territory through military force and that the land taken in this process would not fall under Israeli sovereignty.

In the longer view, this apparent shift in international behavior is marginal and temporary. Shortly after occupying the territory in 1967, Israel began building illegal settlements throughout it.

While the international community held that these settlements were illegal, peace efforts would begin to create a discourse that would reshape consensus over what was legitimate and what was not.

A key example of this is the Clinton parameters issued after American President Bill Clinton failed to mediate a peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians. These parameters marked a diversion from the post-1967 international consensus built with layers upon layers of international resolutions, laws and statements since that time regarding the territory.

In these parameters, a new concept emerges; certain settlements should remain under Israeli control, conferring upon them a previously unearned legitimacy. While the parameters were never implemented, the concept put forward in them regarding the legitimacy of certain settlements remained.

Compounding this was an additional concept regarding the division of Jerusalem, also put forward in the parameters; that which is populated by Jews will remain under Israeli sovereignty while that which is populated by Arabs will fall under Palestinian sovereignty.

|

If Israel could create facts on the ground, by hook or by crook, the international community would ultimately have to recognise it |  |

The message the Israelis got was once again that of the Balfour Declaration and that of the Partition Plan; if they could create facts on the ground, by hook or by crook, the international community would ultimately have to recognise it.

It should come as no surprise that the peace process era resulted in an unprecedented acceleration in the rate of Israeli settlement building.

Indeed, in 2009, the Obama administration began to use the language "we do not accept the legitimacy of further Israeli settlements" with "legitimacy" and "further" being the operative words in this policy statement.

The first word, legitimacy, is in place of what was once a discourse of legality, but that is now avoided as it would open the door to accountability and the possibility of redress through avenues not exclusively controlled by Israel or its key ally, Washington.

The second word, "further" lays down a new temporal marker for the policy that makes it seem settlements built before that would be exempt from inclusion in even the illegitimate category.

While momentum seems to be building toward the Obama administration making some sort of last ditch effort on the Israeli-Palestinian issue, there is great reason to be concerned that the effort, regardless of its intentions, will only ultimately serve to moving the goalposts once again and conferring a sense of legitimacy on another stage of Israeli land grabs.

We've heard, in recent years, a different level of outrage directed at Israeli settlement outposts versus the expansion of settlement blocs as well as a different level of outrage toward settlements expanding onto public versus private Palestinian land.

These differentiations, by obfuscating the reality that all Israeli settlement activity beyond the green line is illegal under international law, provide an aura of legitimacy to the "lesser" violations.

While it is still unclear what President Obama will do on this issue in his final few months, it is not likely to restart a meaningful process that can achieve a just peace, but it is very possible that statements or provisions included in whatever the President does will be used by Israel to legitimise the next foothold in what has been a century-old brick-by-brick, home-by-home process of colonising Palestine.

If the President is considering something along these lines, he should keep in mind the old maxim: "if you have nothing good to say, say nothing at all".

Dr. Yousef Munayyer is a Middle East Analyst at Arab Center Washington DC and Executive Director of US Campaign to End the Israeli Occupation

Follow him on Twitter: @YousefMunayyer

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News